Massachusetts Electricity: Why We Pay So Much—and Why “Relief” Isn’t Relief

Rates nearly double the national average from policy charges and mandates. Temporary cuts, repaid with interest and no opt-out, just defer the burden.

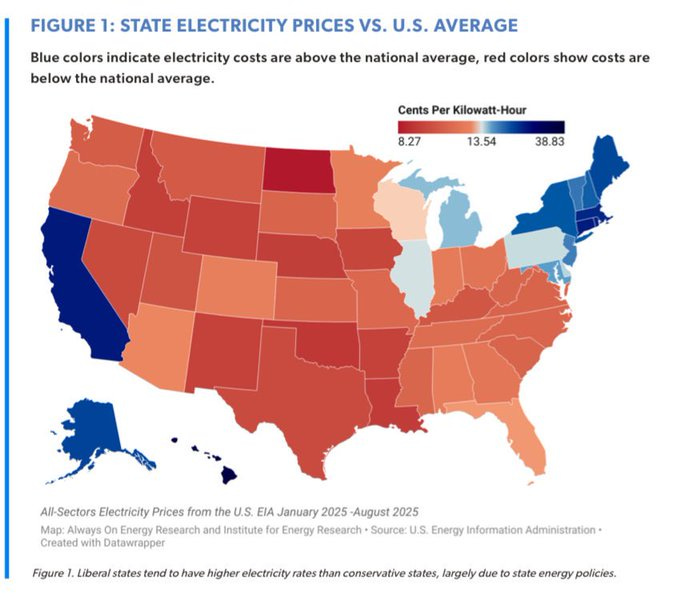

Residents of Massachusetts face a stark reality when it comes to electricity costs. Recent data shows residential rates hovering around 31 to 34 cents per kilowatt-hour, significantly above the national average of approximately 17 to 18 cents per kWh. This places the state consistently among the top three or four most expensive in the nation for residential electricity. In contrast, many states in other regions, particularly those often associated with different political leanings, see rates far lower—sometimes as little as 8 to 12 cents per kWh in places like North Dakota, Idaho, or parts of the Midwest and South.

The disparity can reach three to four times higher in Massachusetts compared to the lowest-cost states. For an average household using around 550 to 600 kWh per month, this translates to bills that frequently exceed $160 to $200, while similar usage elsewhere might cost half as much or less. These differences persist despite Massachusetts possessing advanced infrastructure, access to diverse energy resources through regional grids, and a deregulated market that theoretically allows consumer choice in suppliers.

The core issue lies not in a lack of technology or natural resources but in a series of policy choices that have shaped the electricity market. Massachusetts has pursued aggressive clean energy goals, including a renewable portfolio standard requiring a growing percentage of electricity from renewables—targeting at least 35% by 2030—and participation in carbon pricing programs like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. These initiatives add surcharges to bills for programs funding solar incentives, energy efficiency efforts such as Mass Save, electric vehicle infrastructure, and other mandates.

Analyses indicate that such policy-related charges have increased dramatically over the past decade, quadrupling in some estimates and now comprising a substantial portion of monthly bills—sometimes nearing a third of the total cost. These fees support renewable integration, efficiency programs, and grid upgrades to accommodate electrification and variable renewable sources. While these efforts aim to reduce long-term environmental impacts and transition away from fossil fuels, they impose immediate and ongoing costs on consumers through layered charges that appear on utility statements.

The state’s reliance on imported natural gas for much of its power generation adds vulnerability to price fluctuations, exacerbated by limited new pipeline infrastructure in recent years. Past decisions to block certain pipeline projects have contributed to supply constraints, keeping natural gas—and thus electricity—prices elevated during peak demand periods. Combined with mandates for grid modernization to support electrification and renewables, these factors drive up delivery and transmission charges, which utilities pass directly to ratepayers.

Recent winter challenges have highlighted the strain. Abnormally cold weather and high demand led to spikes in bills, prompting temporary interventions. In early 2026, the governor announced reductions—25% on electric bills and 10% on gas bills for February and March—to provide immediate relief amid affordability concerns. The state allocated funds to cover part of these cuts, but utilities are recovering the deferred amounts from customers in subsequent months, often with interest charges applied to the recovered portions. No opt-out exists for most customers, meaning the “relief” effectively shifts costs forward rather than eliminating them.

This approach has drawn criticism as it does not address root causes. Instead of reducing underlying charges, it creates a repayment mechanism that adds to future bills. Utilities have indicated they will apply interest in most cases, turning short-term savings into longer-term obligations. Such measures underscore a broader pattern: policies that prioritize ambitious environmental targets while leaving ratepayers to finance them through their monthly payments.

Hidden surcharges and mandates accumulate quietly. Renewable energy charges fund clean energy centers and incentives; distributed solar charges support rooftop installations; efficiency surcharges back widespread retrofit programs. Even non-participants pay, as these are system-wide requirements. The result is a bill structure where generation costs are only part of the equation—delivery, policy charges, and recovery mechanisms dominate.

If the goal is truly lower costs, alternatives exist. Removing or capping non-essential surcharges could provide direct relief. Enhancing competition in the deregulated supply market might allow more consumers to shop for lower rates, though supply prices remain influenced by regional wholesale markets. Streamlining permitting for infrastructure—such as additional transmission lines bringing in lower-cost hydropower from Canada—could stabilize supply and reduce volatility. Prioritizing ratepayer interests over expansive spending mandates would shift focus from rewarding additional programs to encouraging efficiency and cost control.

Frustration among residents stems from visibility: people see neighboring or comparable states achieving affordability without sacrificing reliability, while Massachusetts bills reflect accumulating policy layers. Affordable electricity should not feel out of reach in a state with strong economic fundamentals and innovative capacity. The path forward requires balancing environmental ambitions with practical affordability, ensuring policies do not disproportionately burden households already facing high living costs.

True progress would involve scrutinizing each added charge, evaluating its necessity, and exploring funding mechanisms outside ratepayer bills—perhaps through general revenue or targeted incentives. Until then, the pattern persists: layered requirements drive expenses upward, temporary fixes offer brief respite, and consumers bear the long-term load. Massachusetts has the tools and resources to deliver reliable, reasonably priced power. The question remains whether decision-makers will prioritize stripping away unnecessary burdens to make that a reality for everyday residents.

Support my run for State Representative - 9th Bristol District in Massachusetts

This nails it. Moved from North Carolina where rates were under 12 cents, now I'm paying triple here in Boston. The temporary releif with interest is insulting, and my neighbor calculated he'll actually pay more over the year. Your breakdown of those policy surcharges realy exposes how much is just mandated spending.